I saw my reflection on an IMAX screen this Easter Sunday—not my face, but my bloodline. Watching Sinners, Ryan Coogler’s latest film, was less a movie-going experience and more a spiritual reckoning. As the credits rolled, I sat unmoved in the darkened theater, my ancestors still whispering in my ear. Sinners is about a lot—music, folklore, vampires, the resilience of Black Southern communities—but more than anything, it’s about inheritance. And mine runs deep.

At the film’s heart is Sammie, a character played by Miles Caton, whose gift for music defies time and logic. What most wouldn’t know, unless you know me, is that Sammie was inspired in part by my family—specifically my maternal grandfather’s first cousin: Robert Johnson, the bluesman of myth and mystery, said to have sold his soul to the devil for mastery of the guitar. That myth—seductive and sinister—has trailed our family name for generations. But the truth, as passed down through my grandfather George Ball, paints a very different picture.

Johnson wasn’t a man cursed or possessed. He was brilliant, curious, magnetic. He and my grandfather came up in the Mississippi Delta, that hothouse of Black musical innovation. They’d sit on the porch, sharing a Coke, strumming and humming into the dusk. My grandfather, the younger of the two, followed Johnson wherever he could, entranced by his older cousin’s talent. That voice, he’d say, was “beyond anything anybody had ever heard.” A twang from another world.

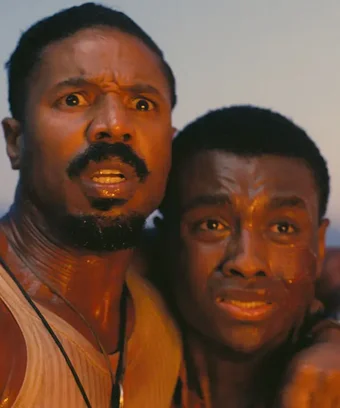

*Sinners* conjures that otherworldly energy. The story follows twin brothers Elias and Elijah—Stack and Smoke—both played by Michael B. Jordan, who return to Clarkesdale, Mississippi, with dreams of opening a juke joint. The space they create is more than a nightclub; it’s a sanctuary. It’s where, for one night, music frees everyone in the room from the weight of Jim Crow. Sammie plays, and time bends. Through his performance, Coogler takes us on a cultural journey through the blues and beyond: African tribal rhythms, gospel’s rebellious twin, the birth of rock, soul, funk, hip-hop. In one scene, African griots dance in celebration of a sound that belongs to them, to us.

That moment broke me open. It was both cinematic spectacle and sacred rite. As Sammie played, I saw my people—living and dead—rise. I saw my grandfather. I saw Robert. I saw myself.

Coogler understands that true storytelling isn’t just about retelling trauma, though our history is marked with it. He speaks instead to the full range of Black humanity. Sinners was born from personal grief—Coogler’s own uncle, a blues-loving man from Mississippi, passed away and became a muse. Like my family, his had moved North and West during the Great Migration, seeking opportunity. Some of us made it. Some of us didn’t. But what often gets left behind in these conversations is what we carried with us: brilliance, grit, and the power of our art.

In an interview, Coogler said something that struck me: “To completely look away [from the South] is to not look at what else was there. The resilience, the brilliance, the fortitude, and also the art.” Sinners doesn’t flinch from the horror, but it makes room for the light too—for joy, for faith, for ancestral power.

And it’s deeply personal. Watching the character Annie (Wunmi Mosaku), Smoke’s lover, I saw my grandmother Amelia Ball. She was a healer, with her hands, her prayers, her olive oil. She warned us, “the devil is busy,” not out of superstition but as a reminder to stay spiritually vigilant. She believed that sacredness was everywhere, especially in how we protected our own.

I’ve never believed Robert Johnson sold his soul. I believe the devil was always nearby, as he is whenever a Black artist reaches toward freedom. The myth of a deal with the devil was easier to accept than the idea of a young Black man finding God not in the pews, but through a six-string guitar. That idea frightened people. Maybe it still does.

This week, Sinners opened to $61 million globally—an undeniable box office win—but outlets like Variety seemed determined to dull the shine. Rather than celebrating Coogler’s triumph, they cast doubt, framing the film as “not yet profitable” and questioning the director’s groundbreaking ownership deal with the studio. The same publications that praise mediocre white-led films for doing similar numbers suddenly forgot how to cheer.

But Sinners is a cultural breakthrough, not just for its numbers, but for how it’s reshaping expectations. Coogler is showing us a new model—Black art, on its own terms, owned by its creator, rooted in history yet leaping into myth.

That, to me, is generational wealth.

My grandfather passed when I was too young to know the full scope of his blues, but I felt it anyway—in family stories, in old records, in the Robert Johnson room my aunt curated like a shrine in her Maryland home. I’ll be returning there soon, on the anniversary of my grandfather’s death, and now I’ll carry with me the memory of that scene, that sound, that spiritual rupture that reminded me: the blues didn’t just birth music. The blues birthed me.

In watching Sinners, I finally understood the depth of what I’ve inherited. Not just talent or legacy, but a lineage of resistance, beauty, and boundless creativity. My family didn’t just witness history. They sang it into being.